By Neil Cuthbert and Atif Choudhary, Dentons

The project was initially launched by China’s President Xi Jinping in late 2013 as one of the Asian superpower’s ambitious plans to accelerate outbound investment and to consolidate its position generally across the globe. Physically, OBOR is best understood with reference to its two key tangible cornerstones. The first is an overland route from China through to Western Europe, sweeping through South and South-East Asia, Russia, the Persian Gulf, the Middle East, North Africa, the Mediterranean and in between. This has been dubbed the New Silk Road Economic Belt. The second comprises a maritime route which runs southbound down the east coast of China, through the South China Sea and into the South Pacific before heading westbound through the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea to Europe. The primary purpose is to create a gateway for China’s burgeoning capital and other resources in a manner and on a scale not seen before. Once the wheels of OBOR are fully set in motion it will lay a platform for economic investments in almost every sector, but with an inclination towards infrastructure and trade. Following the launch of OBOR, many nations along its path have rushed to enter into bilateral treaties and agreements with China. To date, China has entered into well over 30 such agreements and trade negotiators are working on overdrive to increase this number, including significant deals with countries such as Russia, Turkey, India and Pakistan, which goes some way to showing just how seriously OBOR is being taken among some of the regions and the world’s economic heavyweights. Current investment in OBOR The ink has barely dried on the establishment of the Silk Road Fund, yet it has already kicked into gear with its first investment being in the multi-billion dollar Karot hydropower project in Pakistan in early 2015. Later that same year the Silk Road Fund entered into a formal agreement by way of a Memorandum of Understanding with Russia’s Vnesheconombank and the Russian Direct Investment Fund for the construction of energy infrastructure projects. Subsequently it has also taken a stake in Novatek’s Yamal LNG project in Russia and made an investment in Italian tyre producer, Pirelli. |

Although not formally tied to OBOR, the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), with headquarters in Beijing, can naturally be seen as an institution which will back OBOR with some strength. The AIIB was established with the backing of 57 prospective founding members, although this number is set to rise with other states who do not hold such status showing an interest in becoming members. These states include influential powers such as the UK, France, Italy and Germany. With initial capitalisation to the tune of US$100 billion and room to grow significantly, the AIIB is already being spoken of in the same breath as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank.

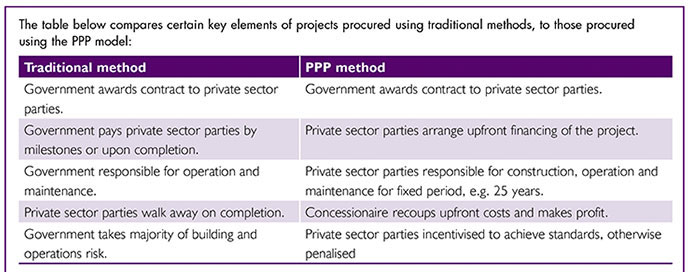

OBOR and the PPP model

With many OBOR projects being regularly launched, issues and questions will arise as to how best to structure them. Some of the more difficult large-scale projects will be funded through government-to-government grants, others will utilise the traditional export credit models, such as buyer credits and supplier credits, and some will use the increasingly popular “EPC+F” structure (engineering, procurement and construction plus financing). However, many will utilise the Public Private Partnership model (PPP) for structural, economic and legal reasons:

Infrastructure gaps

Many of the nations along the Silk Route are underdeveloped nations with a need for foreign investment, with a particular emphasis on infrastructure, particularly through the Asia/South Asia segments of the route. Many of the projects in such nations which are looking to fill their infrastructure gaps are looking for equity investments of the kind which the PPP model strongly supports and which the OBOR strategy will encourage. This is of course a move away from the traditional procurement methods which used to see the engagement of Chinese enterprise solely for their construction capabilities.

Investment through equity interests

The Chinese government itself is now aggressively advocating and encouraging outbound investment in the form of equity stakes in projects and assets across the globe. The OBOR strategy and PPP model complement each other considerably in this respect.

Legal impediments

In many of the nations along the Silk Route the mandatory position for one reason or another is for the host nation to have ownership (or at least strict control) over its own infrastructure. Without the resources to go it alone, the PPP model is an obvious choice for them to meet their infrastructure needs without ceding rights they wish to retain. By awarding a concession they can attract foreign know-how and investment while maintaining ownership (or the right to ownership at a later time).

In certain regions (for example, parts of the Middle East and Africa) we are now seeing that PPP laws and regulations are being implemented and developed in order to support and facilitate the PPP model. In some cases the legal impediments are being broken down in a way which will support the use of the PPP structure. This will, in turn, support OBOR growth.

Joint ventures

PPPs are one of the more convenient and workable project models for contractors who are looking to get into joint ventures with foreign entities. By becoming a partner to governments, rather than mere employees, there is scope for significant mutual benefits to arise. Governments are seeking investors who are willing to commit to their countries for longer terms, and Chinese enterprises are looking to become part of the decision-making process rather than being hindered by it as they historically have been in some countries. PPPs strongly support these objectives.

Project financing

Significant development of late in the project financing arena means that governments, financial institutions and the private sector are becoming more and more comfortable with project financing PPPs. Although numerous PPPs have suffered wobbles in the early days where participants failed to plan and understand the structure adequately, this model is slowly but surely being refined and made more robust to the point where PPPs are now regularly achieving a successful financial close, including many involving Chinese interests. Chinese companies are becoming increasingly comfortable with this model, helped in a small part by the explosion of PPP projects within China over the last 24 months.

The further development and refinement of project financing techniques will be an important factor in the successful implementation of OBOR projects.

KEY CHALLENGES FOR OBOR

China’s true agenda?

A key challenge already being faced by China is doubts over the true motivations behind its OBOR vision.

It is ultimately important to remember that OBOR is so much more than being about just infrastructure and economics. It also encompasses China’s future role in the world, promoting its ideas and philosophies and demonstrating how China can cooperate with the rest of the world and build mutually beneficial partnerships with other countries.

Funding

When OBOR is considered in its totality, we must cease discussions about billions or even hundreds of billions of dollars — OBOR is well and truly in the trillions category when it comes to cost and impact. How can China afford it? The short answer is that it cannot do it alone. The reality is that the amounts contributed so far fall well short of what is and will be required in the coming years. And all this is at a time when things are becoming fiscally more challenging for China.

In addition to the funding challenges which any project of the scale of OBOR would have, there are certain specific challenges that OBOR will face. For example, how does one attract investment to high-risk countries such as Pakistan, Afghanistan and Syria? Will Western financial institutions, shackled as they are by EU and US regulations, collaborate with Chinese institutions to help finance OBOR?

Legal Competition or cooperation? The early signs coming out of China are positive and signal China’s intent that it will cooperate and collaborate with its peers. However, results are what will ultimately matter to those watching. Conclusion — is the Silk Road paved in gold? Despite the best of intentions and efforts, it is without doubt that there are numerous challenges which lie in OBOR’s path. Some can be considered obvious and inherent in a project of this scale; others will emerge and evolve in the years and decades ahead. What is clear, however, is that the potential benefits for all involved are immense. Crucial infrastructure that otherwise might take decades to deliver is now seemingly in a position to be delivered on an accelerated timetable and the consequential benefits this can bring about are endless. So yes, the Silk Road is potentially paved in gold, both for China and for those countries that embrace this initiative and the potential benefits that it brings. |

E: neil.cuthbert@dentons.com • atif.choudhary@dentons.com

W: www.dentons.com/en.aspx