The dean of Peking University School of Transnational Law in Shenzhen discusses the development of legal education in China.

Asian-mena Counsel: What is the background of the Peking University School of Transnational Law, Shenzhen (STL) — when was it founded and what is its purpose?

Philip McConnaughay: STL was established in 2008 by special authorisation of China’s State Council. The founding dean was Jeffrey Lehman, a former president of Cornell University and dean of the University of Michigan Law School. The idea was to establish an American-style law school at China’s leading university that would be accredited by the American Bar Association [ABA]. The goal was to provide China’s top students the option of earning an internationally recognised Juris Doctor degree in China, while simultaneously providing an educational model that would help advance legal education and the legal profession in China.

STL took a detour of sorts in 2012 after the ABA refused to extend its accreditation jurisdiction outside of the US and Puerto Rico, and founding dean Lehman left to establish NYU’s Shanghai campus. That’s when I joined STL. We retained STL’s original purpose of providing an elite graduate-level common law JD education in China, but we expanded our mission by reforming and elevating our China Law Juris Master [JM] curriculum to include the “case study” and Socratic questioning methods of instruction typical of American legal education, both of which represent significant innovations in China legal education, and emphasising the new transnational legal and commercial principles likely to emerge from the rapidly expanding economic exchange between China and the West.

Most recently, we have been adding elements to our curriculum that focus on the legal and commercial traditions of Central and South Asia and the Middle East, all regions of growing importance in terms of China’s economic engagement.

Most recently, we have been adding elements to our curriculum that focus on the legal and commercial traditions of Central and South Asia and the Middle East, all regions of growing importance in terms of China’s economic engagement.

The evolving economic integration of Shenzhen and Hong Kong, together with Shenzhen’s role as a gateway for China’s Belt and Road Initiative, offers what is probably the world’s most exciting and dynamic legal environment for STL’s unique approach to legal education.

In a nutshell, STL’s dual Common Law JD-China Law JM programme, which is unique in China and the world, has been wildly successful. Demand for STL graduates among China’s and the world’s leading law firms, multinational companies, government offices and NGOs is so high we are not able to meet it. We have negotiated alternative routes to American bar exam access for STL students that do not depend on ABA accreditation. There is keen interest in STL’s approach to legal education both within China and worldwide, and we are beginning to see other law schools emulate aspects of our approach. Perhaps most gratifying, STL graduates are becoming leaders of China’s growing legal profession, fully equipped to handle the sophisticated transactions and disputes increasingly characteristic of China’s advanced internationalised economy, traditionally almost exclusively the province of blue-chip Anglo-American firms.

AMC: How has the legal profession changed since you first graduated? Does STL provide all the training required for the ‘modern’ lawyer, or are there areas for improvement?

PM: The legal profession has undergone multiple changes since I first began practising law, both in the nature of services required and in methods of delivery. The demographics of the profession (thankfully), the rise of technology and electronic discovery, the use of alternative billing methods, the ability to work and partner remotely, and many other aspects of the profession all have changed quite dramatically. Although much of the law remains local and geographically defined and applied, the change I view as most fundamental has been the internationalisation of legal services. The best lawyers today are those prepared to contend fairly and knowledgeably with the interaction between different legal systems and traditions, and with the often fundamentally different expectations of parties from different traditions. Today’s lawyers must be prepared to acknowledge, respect and help find solutions when different traditions and expectations — even, at times, different notions of truth and justice — are present in a single transaction or dispute. I view this as both an intellectual and ethical responsibility of the profession. Yes, I believe STL prepares our students for this challenge.

PM: The legal profession has undergone multiple changes since I first began practising law, both in the nature of services required and in methods of delivery. The demographics of the profession (thankfully), the rise of technology and electronic discovery, the use of alternative billing methods, the ability to work and partner remotely, and many other aspects of the profession all have changed quite dramatically. Although much of the law remains local and geographically defined and applied, the change I view as most fundamental has been the internationalisation of legal services. The best lawyers today are those prepared to contend fairly and knowledgeably with the interaction between different legal systems and traditions, and with the often fundamentally different expectations of parties from different traditions. Today’s lawyers must be prepared to acknowledge, respect and help find solutions when different traditions and expectations — even, at times, different notions of truth and justice — are present in a single transaction or dispute. I view this as both an intellectual and ethical responsibility of the profession. Yes, I believe STL prepares our students for this challenge.

AMC: In an era where we are encouraged to countenance multiple careers, your own has included not only being one of the only foreigners to hold a leadership position at Peking University, but also a senior partner at Morrison & Foerster (MoFo). How does a career in academia compare to a career in corporate law?

PM: Well, I have been very fortunate in that both aspects of my career, practising law and academics, have been incredibly interesting and rewarding. The thing I enjoyed most about practicing law is the constantly changing problems of significance that lawyers help address. My academic career really has had two dimensions, being professor and teacher, on the one hand, and being a law school leader, on the other. Being a professor provides a unique opportunity to think and write about issues independently of the interests of a client, and to contribute to the education of future lawyers. I have enjoyed both of these things very much. Leading a law school calls upon so many of the skills of practice — strategy, negotiation, sometimes adversarial negotiation — in addition to a knowledge of legal education that it’s almost as if my two professions have converged.

AMC: Your work at MoFo included helping to lead the MoFo team representing Fujitsu in its international arbitration with IBM. What was the significance of Fujitsu’s eventual victory?

AMC: Your work at MoFo included helping to lead the MoFo team representing Fujitsu in its international arbitration with IBM. What was the significance of Fujitsu’s eventual victory?

PM: I’ll mention two aspects of the IBM/Fujitsu arbitration that I believe have had lasting significance and that, I should add, were achieved because of the efforts and ingenuity of both parties, both teams of lawyers, and the arbitrators. The first was the creation of a unique model for the management and resolution of a complex worldwide dispute involving multinational parties, the interests of multiple nations, and no clear applicable law. The IBM/Fujitsu arbitration was so large and complex that we essentially had to devise our own rules of procedure, applicable law and rules of engagement. It was a unique combination of arbitration, mediation and constant negotiation, in which the parties, arbitrators and lawyers happily shared a very forward-looking orientation. The process was far more about finding solutions than it was about imposing blame. The second was the principle of interoperability and the singular importance of clearly defined interfaces to interoperability. This was a major advance for worldwide consumers and producers of high technology.

AMC: Your academic writings are diverse and include a thoughtful piece on China’s impact on the Western legal tradition. Can you share some of your thoughts on this topic?

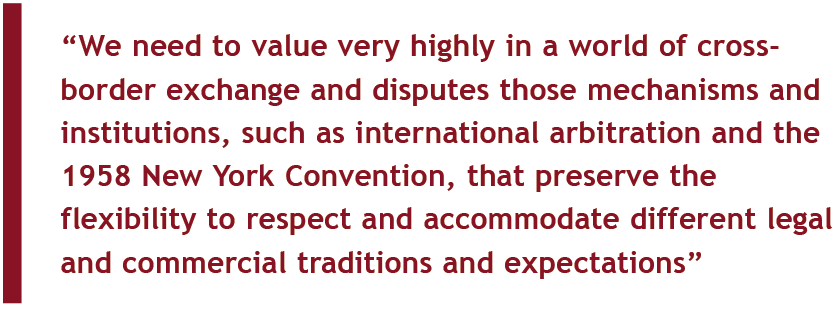

PM: I’ll share one. I do not believe in the eventual convergence of all law and legal practice around the Western legal tradition. We need to value very highly in a world of cross-border exchange and disputes those mechanisms and institutions, such as international arbitration and the 1958 New York Convention, that preserve the flexibility to respect and accommodate different legal and commercial traditions and expectations, as well as the new traditions and expectations likely to emerge from their interaction. My views about this are informed both by my years of practice representing non-US parties and interests, and by my experience helping to establish one of China’s most innovative and successful programmes of legal education.

AMC: As one of the seers relating to the exponential growth of Shenzhen and the emergence of the Greater Bay Area, how do you see its development comparing to Silicon Valley and the original Greater Bay Area in California?

AMC: As one of the seers relating to the exponential growth of Shenzhen and the emergence of the Greater Bay Area, how do you see its development comparing to Silicon Valley and the original Greater Bay Area in California?

PM: I’ve been fortunate to be a first-hand witness to the emergence of both areas. China has provided a modern, interconnected infrastructure for the Greater Bay Area — transportation, communications and energy — that, in my view, is likely to ensure the eventual expansion of the innovation and development characteristic of Shenzhen throughout the region. China also is doing an admirable job of experimenting with the best approaches to laws and judicial and regulatory institutions most conducive to sustaining the advanced, innovative, internationalised economy of the region. The one ingredient of technological innovation in which Shenzhen and the Greater Bay Area still lag in comparison to California’s Silicon Valley and other US centres of innovation is higher education. The Greater Bay Area needs more institutions of higher education, and higher education throughout China, in my view, needs more autonomy if it ever hopes to match the creative output of the US.

AMC: Who was your mentor?

PM: In law practice and client service generally, two senior partners of Morrison & Foerster, the late Bob Raven and Jim Paras. I’ve never known finer, more ethical lawyers with a better understanding of the profession.

AMC: What advice would you give to a young lawyer entering the profession?

PM: Be honest. Be ethical. Leave no stone unturned. And, underestimate neither the complexity of the law nor the value of compromise.

AMC: What is your hinterland?

PM: I’ll interpret this literally as asking for my favourite remote area. This is probably the Indian Ocean Coast of the Margaret River region of Western Australia. I have many close “second” favourites all over the world, but the Margaret River region probably tops my list.

____________________________

Philip McConnaughay is dean and professor of law of STL and a vice-chancellor of Peking University’s Shenzhen Graduate School. Before joining STL, he was founding dean of Penn State University’s law school and School of International Affairs. Prior to joining Penn State, he was a professor of law at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and before that a partner of the international law firm, Morrison & Foerster, resident for almost 10 years in Tokyo and Hong Kong. McConnaughay is the author of numerous scholarly articles and edited books concerning international commercial dispute resolution, the regulation of international commerce, and the role of arbitration in economic development. He serves on the editorial board of the Indonesian Journal of International & Comparative Law. As a practising lawyer, McConnaughay was involved in some of the major antitrust and intellectual property disputes of the day. He has served as an adviser to the government of Indonesia with respect to the drafting of a new national arbitration law, and has been active throughout his career in a variety of public interest and pro bono matters.