Living and working as a lawyer in the US, Asia, Europe and Australia for over 30 years, my legal knowledge and skills were the foundation of my career. But, more than anything, it was a range of non-legal skills and competencies that really helped me to change the way I worked. They allowed me to make more of an impact, enjoy my work more and ultimately be more successful. I’d like to say that it was all part of a master plan, but it wasn’t. It was largely opportunistic and unstructured.

I thought to myself that it doesn’t need to be that way for other lawyers. So, in 2015, I decided to form AlternativelyLegal and share my experiences through a program that I initially called Everything But The Law. Back then, only a few people were talking about the importance for lawyers to develop, and to know how to use, non-legal skills such as process improvement, design thinking, business partnering and change management.

A lot has changed over the last five years and especially the last twelve months.

At a macro level, there has been a general recognition of the importance for all workers to develop what are often referred to as ‘soft skills’.[i]

Also, as the World Economic Forum’s Report on the Re-skilling Revolution[ii] highlights, there is a critical and widespread need to re-skill and up-skill to anticipate the advance of technology and adapt to new roles and ways of working. Re-skilling involves learning new skills and competencies for potential new roles and up-skilling involves learning new skills and competencies for career progression within the same role.

Does this apply to lawyers or are lawyers somehow exempt from all of this?

Many tasks that lawyers did in the past—such as legal research, document due diligence, contract review and, even, assessing the prospects of success in a dispute—can today be done, or facilitated, by technology. As Richard and Daniel Susskind point out in their book, The Future of the Professions[iii], increasingly capable machines relentlessly encroach on tasks performed by lawyers and other professionals and, over time, no task is off limits.

Looking at this up-skilling imperative from a different angle, there have been many studies of late that confirm the critical importance for lawyers to develop non-legal skills and competencies. For example, The Foundations For Practice: The Whole Lawyer study in the US, based on surveys of over 24,000 lawyers, found that characteristics and competencies were more important than technical legal skills. As the report states, “We no longer have to wonder what lawyers need. We know what they need and they need more than we once thought. Intelligence, on its own, is not enough. Technical legal skills are not enough. They require a broader set of characteristics, professional competencies and legal skills that, when taken together, produce a whole lawyer”[iv]

It is now no longer controversial to say that focusing just on your legal knowledge and technical skills might have got you where you are today, but it won’t get you to where you want to be in the future. The debate now is about what specific subject areas are critical and how best to provide education, training and development in these areas.

Many universities around the world now offer various non-law elective subjects such as design thinking and technology-related topics. Others offer more comprehensive undergraduate and postgraduate courses[v] that are typically framed around innovation or technology that include a variety of non-legal subjects.

Universities and other tertiary institutions can, and should, be a key part of the solution to this up-skilling and re-skilling challenge. However, in a world where lifelong learning is now essential and where different types of more applied training and development are required for different career paths, other organisations must also contribute.

Historically, law firms have played a valuable role in continuing the development of lawyers after they graduate but that role may diminish somewhat as the focus shifts to non-legal areas and as more individuals don’t work in firms as part of their career path. Firms will no doubt continue to provide legal updates, and in some cases legal training, to clients. Recently, I have even worked with a few firms to extend this training to non-legal skills.

To supplement these traditional sources of training, a range of businesses, centres and associations have emerged in recent times offering training courses on non-legal subjects in many countries. In these countries, lawyers now face a different challenge: how to choose between an ever-growing range of training offerings from an ever-growing number of organisations? My clients tell me that this challenge can be quite daunting and, given the limited time and budget available for training and development, they want to be sure they achieve maximum impact from their investment.

One problem with a lot of the training on offer is that it largely ad hoc, focusing on one or two supposedly critical skills or an apparently random combination of skills. How can you know whether what is covered in any program is sufficient and really going to make a difference?

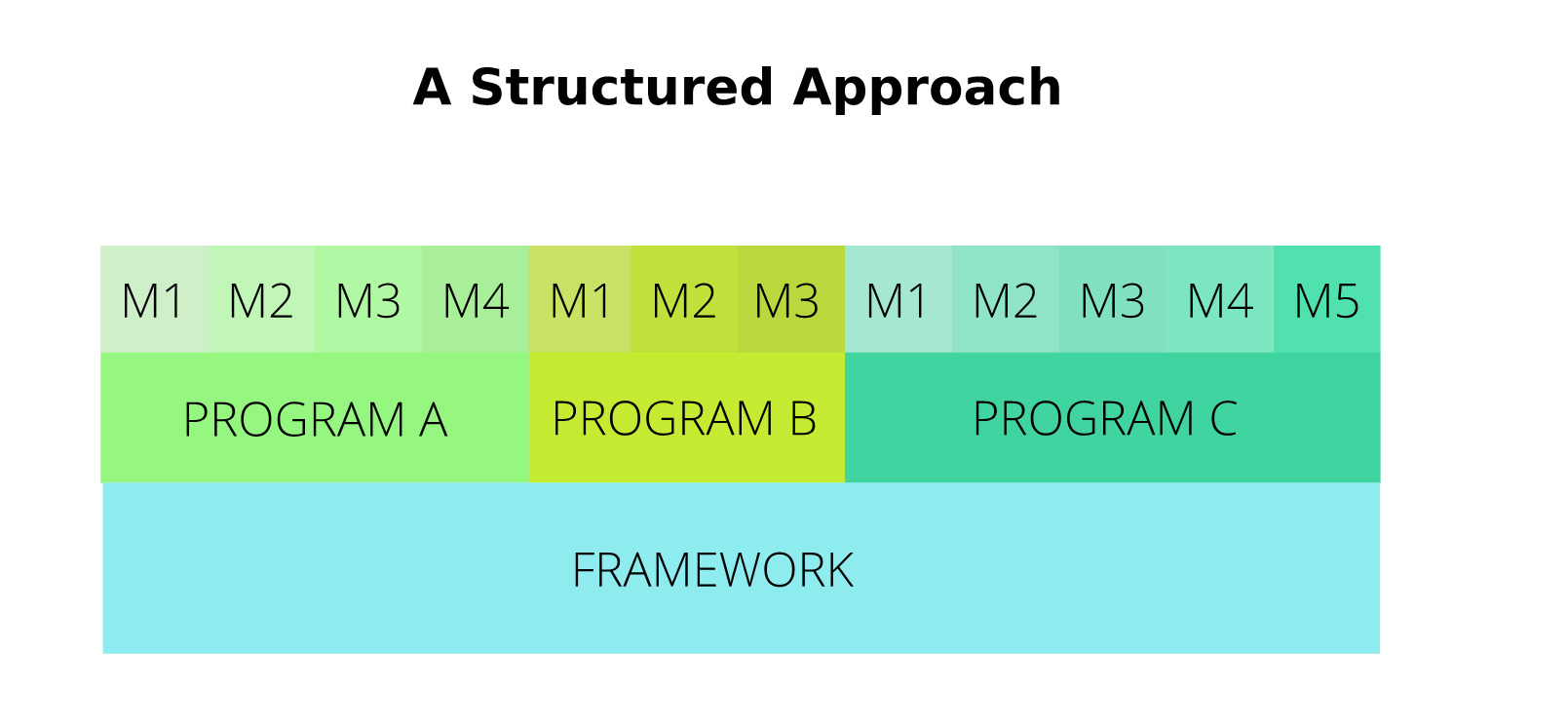

One solution to this problem is to develop a holistic framework that forms the basis of, and provides the structure for, more focused programs and, for each program, a series of detailed modules or courses. Ideally, frameworks targeted at the same audience – for example in-house legal teams and individual in-house lawyers – should align with, and complement, each other. That should also be the case for the individual programs and modules forming part of a framework.

So far, three main potential frameworks or models have emerged for the training and development of lawyers that focus on non-legal skills: The T-shaped Lawyer, The O-shaped Lawyer and the Delta Model. This article will now explain each of these and highlight some key differences.

1. The T-shaped Lawyer

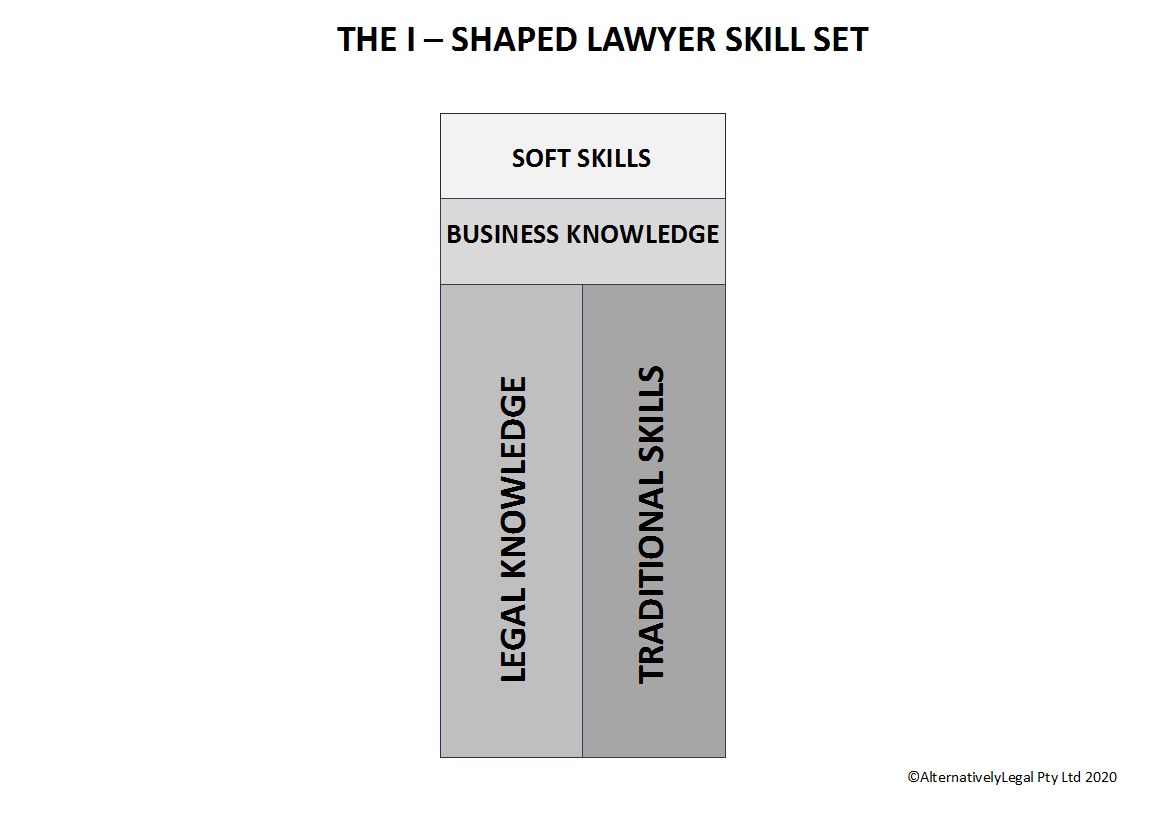

The vast majority of professionals, such as lawyers, engineers or accountants, are referred to as ‘I-shaped’. They typically have deep expertise in one area but little to no skills, knowledge or experience beyond that specialist domain. Lawyers, for example, have deep knowledge of, and expertise in, certain areas of the law and their training and development has historically focused on honing that knowledge and expertise. They might have undertaken some general leadership, business or soft skills training but their primary purpose has largely been to enhance their ability to do traditional legal work.

As noted in a Cambridge University study[vi], the problem with I-shaped professionals is that organisations increasingly need people to work collaboratively in cross-functional teams to innovate and problem-solve for the organisation as a whole or their customers. The study highlighted that the main obstacle for service innovation through cross-functional collaboration is a skill or knowledge gap. To address that issue, this report recommended that organisations should actively develop more T-shaped professionals throughout the organisation. This becomes especially important for the increasing number of companies that are transforming to an agile way of working but it remains important even for those that are not.

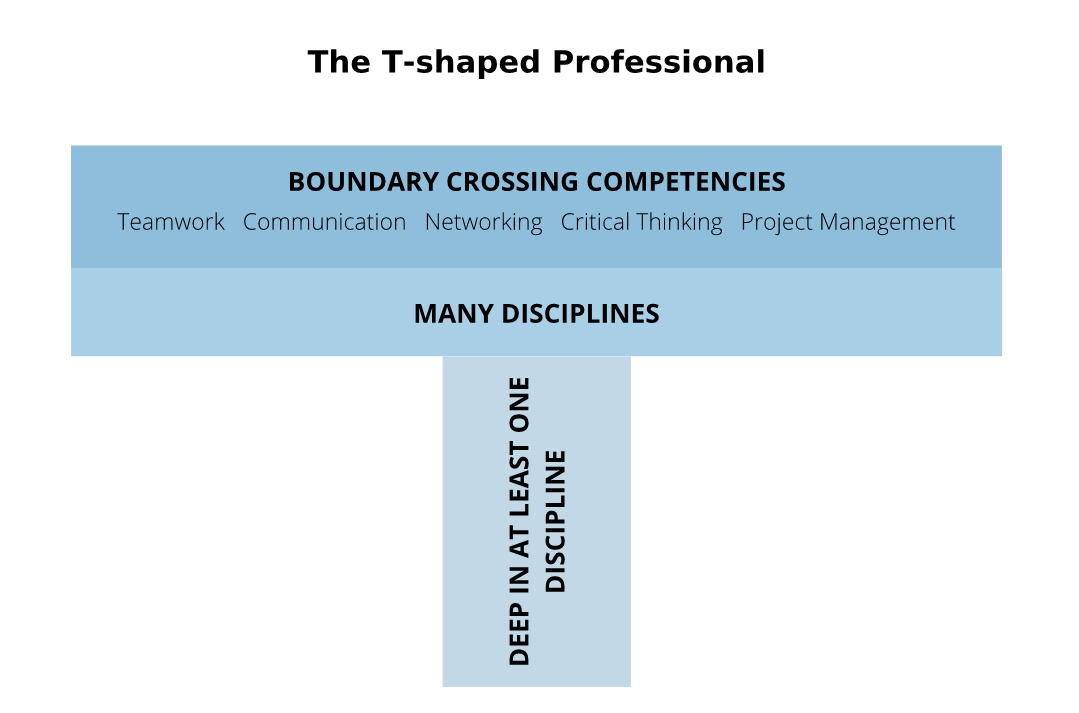

What does a T-shaped professional mean?

A T-shaped professional refers to someone who has deep domain expertise in one discipline, together with various competencies and skills and knowledge from other areas, that helps that person collaborate with specialists from different disciplines to innovate for the organisation as a whole, not just one department. However, the benefits of becoming a T-shaped professional extend well beyond enhanced collaboration to include, for example, being more adaptable and resilient.

References to T-shaped professionals and skills have been around for many years[vii]. Recently, various derivatives have been suggested including the Key-shaped, X-shaped or Pi-shaped professionals. Each of these concepts has some merit. However, the T-shaped concept is by far the most widely recognised and adopted globally throughout the corporate and academic world[viii]. For example, others have taken the high-level T-shaped professional concept depicted above and applied it in more detail for T-shaped individuals, university graduates, employees, engineers, designers, accountants and IT, HR and marketing professionals.

The fact that the construct is so widely used is one of the reasons I chose to adopt it. I believe that lawyers should stop thinking of themselves as special, especially as one of the main objectives of developing non-legal skills is to collaborate with non-legal professionals. However, the main reason I decided in 2016 to use the T-shaped branding is that it provides the perfect basis for my vision and programs for transformation, not just improvement, of individual lawyers and also for legal teams and law firms.

At the same time, I wrote an article called ‘The T-shaped Lawyer’ that was published in various international publications[ix]. I thought that I was the first to make the connection between the T-shaped professional construct and lawyers. However, I subsequently found out that someone—R. Amani Smathers—had written an article and spoken at a conference about it a year earlier. Since then, a number of people have written or spoken about the T-shaped Lawyer.

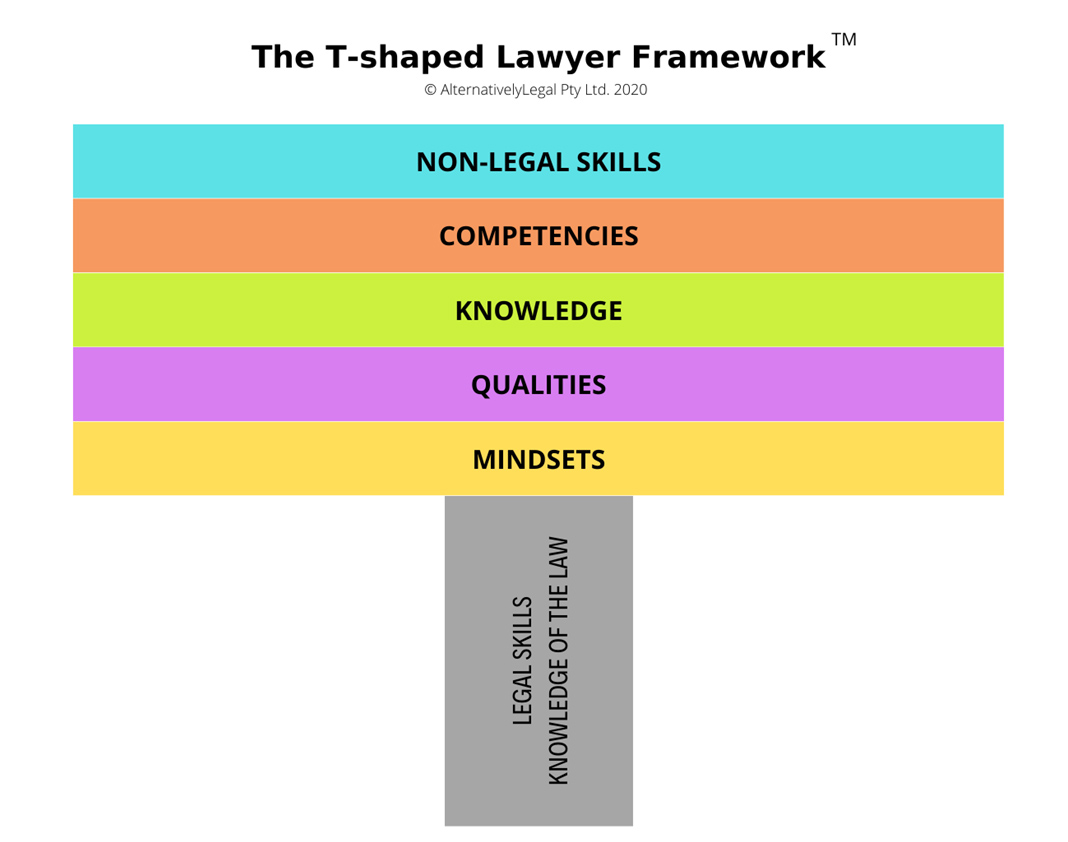

However, as far as I know, I am the only one who has progressed from talking about it as a construct to actually developing comprehensive frameworks and programs for legal teams, law firms and individual lawyers and delivering these programs to over one thousand lawyers worldwide for the last five years. At a high level, the generic framework is as shown below.

There is a lot of detail within each layer of the framework and to explain that is beyond the scope of this article. So far, I have only shared details of the frameworks and program with my clients. But I have decided to make information about the T-shaped Lawyer Framework available more broadly in a book that I plan to publish soon. Stay tuned or get in touch if you’d like to find out more beforehand.

2. The O-shaped Lawyer

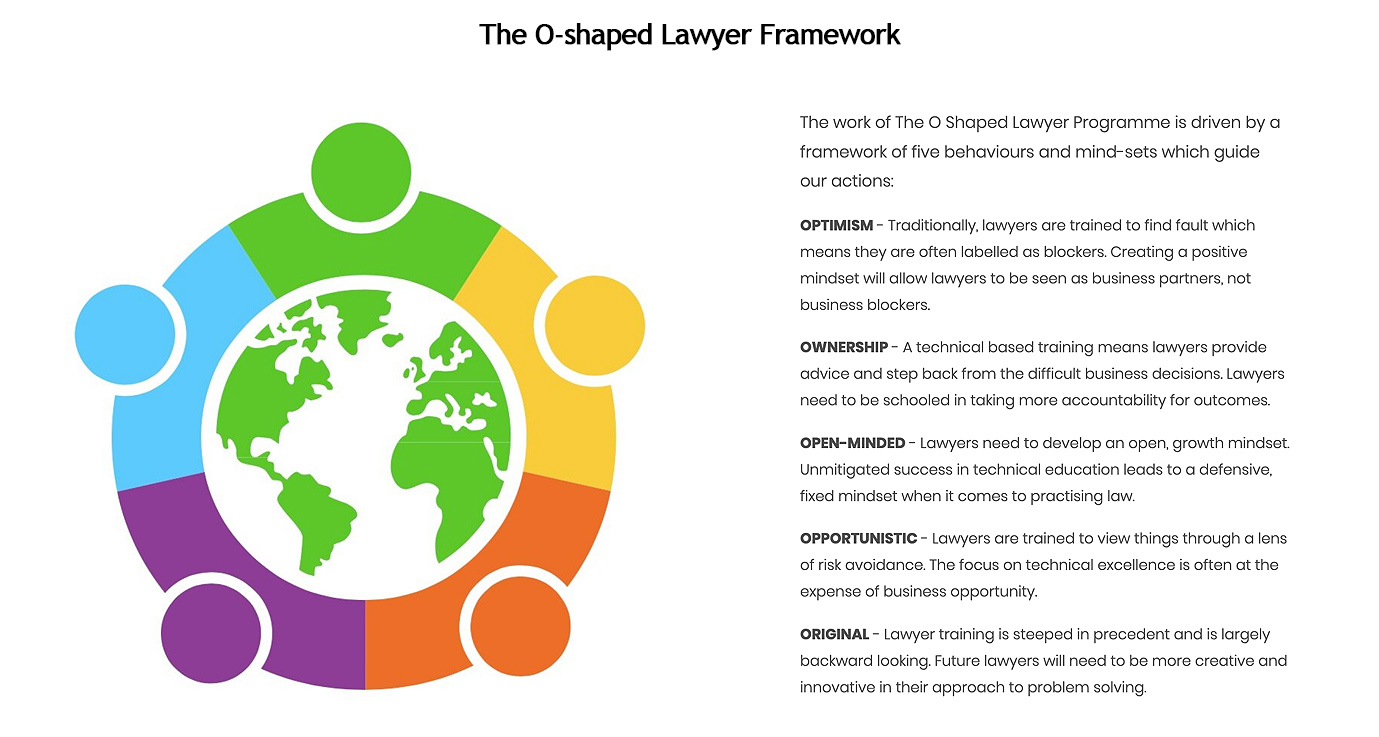

Dan Kayne, general counsel of regions, Network Rail UK recently came up with the idea of the O-shaped Lawyer to develop more well-rounded lawyers by focusing beyond technical legal skills. Late last year he assembled an impressive working group from across the legal profession in the UK and formed The O-shaped Lawyer Program[x]. According to their website, they aim to ‘show that with a greater emphasis on a more rounded approach to the formation of our lawyers, the legal profession will provide its customers with a better service in a more diverse, inclusive and healthier environment.’

The group is seeking to have the O-shaped Lawyer Framework (see below) adopted in two main areas. First, in the early stages of a lawyer’s education at university and in the new Solicitors Qualifying Exam program in the UK. Second, in the ‘practise stream’ specifically to adopt the O-shaped Framework in the engagement between law firms and in-house teams. As I understand it, they are currently attempting to kick start the initiative with some pilots between firms and in-house teams in the UK.

According to this framework, lawyers can develop these ‘O’ behaviours by having a proactive mindset, together with legal, business and customer knowledge and the skills outlined below.

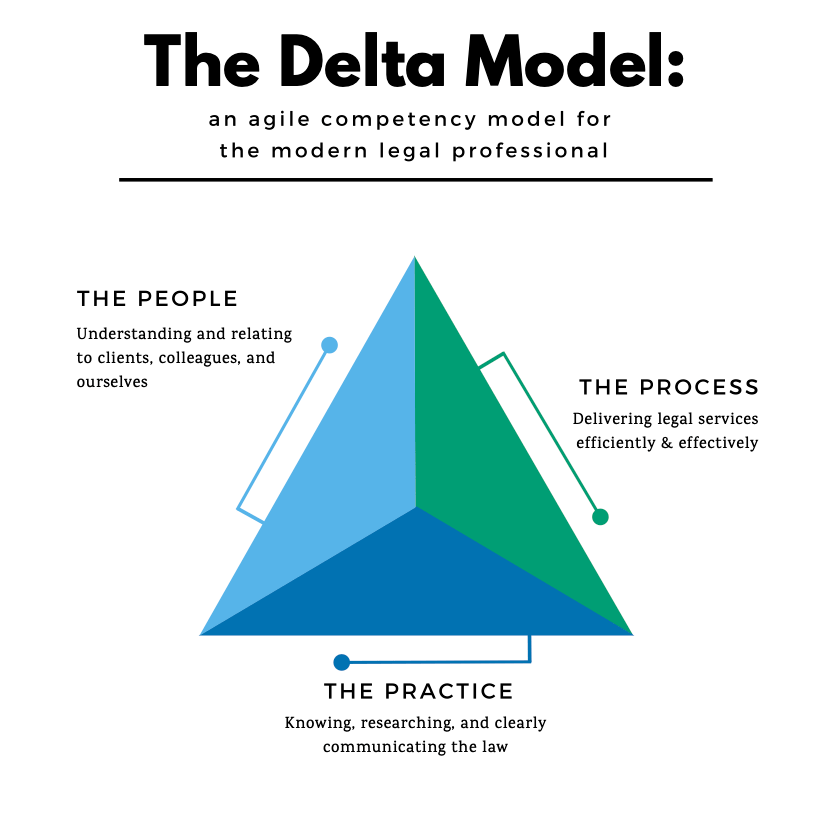

3. The Delta Model

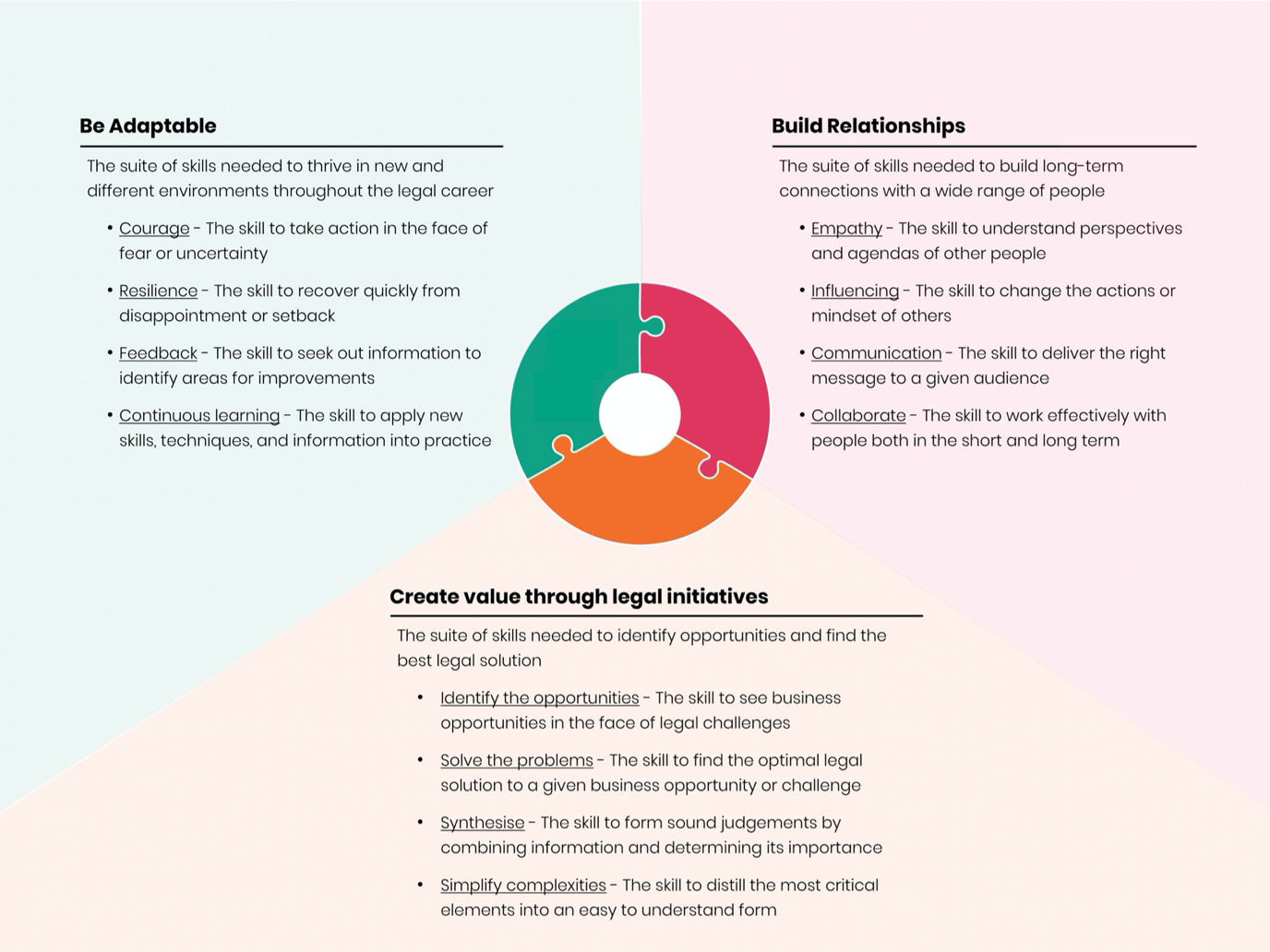

Last year, a diverse group of academics in the US[xi] conducted some empirical studies that confirmed the critical need for lawyers to develop non-legal skills and competencies. They formed a group to devise a competency model that could be used by anyone in, or planning to enter, the legal ecosystem irrespective of whether the role is a legal or non-legal one and also irrespective of the stage of their career.

The group were attracted to the T-shaped concept, but they perceived that it lacks what they originally referred to as the personal effectiveness dimension and what they now call the people dimension. It is true that Smather’s depiction of the T-shaped Lawyer—which is what they were using as their reference point—did not highlight these so-called personal effectiveness aspects. However, these aspects are indeed covered in the general T-shaped professional concept, being explicitly referred to as boundary crossing competencies, and in my T-shaped Lawyer Framework.

The group decided to take the T-shaped concept and modified it into what they refer to as the Delta Model. The model has evolved through several iterations but the latest version at the time of writing this article is as shown below.

Because the Model is still being developed, the details are still evolving. However, we can gain some insight into what is intended to be covered by noting that in the penultimate version of the Model, known as Version 3, the:

- practice dimension was referred to as the Law and was stated to include subject matter expertise, legal research, legal analysis and legal writing

- process dimension was referred to as Business and Operations and was stated to include business fundamentals, project management and data analytics

- people dimension was referred to as Personal Effectiveness and was stated to include relationship management, entrepreneurial mindset, emotional intelligence, communication and character.

Further insights into what is intended to be covered can be found on their informative and helpful site (https://www.designyourdelta.com/) where they refer to some specific competencies as follows:

People competencies – business development, character (accountability, common sense, integrity, professionalism, resilience, work ethic), collaboration, communication (active listening, conflict resolution, interviewing, managing change, speaking/writing persuasively), creative problem-solving, emotional intelligence (empathy, self-awareness, self-regulation), entrepreneurial mindset (adaptability, proactive problem-solving, taking initiative, strategic planning, curiosity), human-centred design, leadership, and relationship management (feedback, coaching).

Process competencies – business development, business fundamentals, data analytics, data security, human-centred design, process selection/design/improvement, project management and technology.

Practice competencies – case analysis, case framing, issue-spotting, legal analysis, legal judgement, legal research, legal writing and subject matter expertise.

Their site also refers to the current effort to develop playbooks that they plan to make available for use by different groups within the legal industry.

So which framework is best?

Although it is obvious where my preference lies, it would be difficult at this time for you to reach a conclusion on this question because details of the programs that underly the O and Delta Frameworks are not finalised, and details of my programs are yet to be broadly publicised.

However, it is worth noting the following points of difference between the three frameworks:

- the primary aim of the T-shaped Lawyer Framework and associated programs is to offer a solution for human transformation, which has so far been overlooked in the current preoccupation with digital transformation. In other words, it outlines a comprehensive vision and means for lawyers to develop new skills, competencies, capabilities, knowledge and mindsets to truly transform what work they do and how they do it, not just improve their current way of working. It is not clear to me whether the same can be said for the other two frameworks that appear to have different purposes

- the T-shaped Lawyer Framework takes a well-known and established concept that is widely used by a range of professionals in the business world and applies it to lawyers. The other two models are being developed by lawyers or legal academics just for those working in the legal industry

the T-shaped Lawyer Framework and associated programs have been refined, tried and tested over many years and in many countries throughout the world for in-house lawyers and in-house legal teams and I am now, in conjunction with a leading firm, in the process of developing it for lawyers working in firms. The other two frameworks and associated programs are still under development and, as far as I know, not yet tested or applied in the real world unlike the O and Delta Frameworks, the T-shaped Lawyer Framework was not originally designed with law students and graduates in mind, although it would be possible to develop such a version - the O-shape is symbolic of the well-rounded person its programs are intended to produce. The three sides of the Delta Model are intended to symbolise change and the three dimensions of education and training essential for anyone working in the legal industry. The T-shape is symbolic of the specific shift that I believe lawyers need to make from narrow/legal to broad/business and from specialist to expert generalist

- the founding group of the Delta Model are high profile academics in the US, which is likely to help their efforts to have their model adopted. The O-shaped Lawyer movement has the support of some general counsels and a few law firms in the UK and that, too, will likely assist their efforts to have their model adopted. The T-shaped Lawyer Framework is not that well known other than to the legal teams and law firms around the world that have participated in my programs. That is one of the reasons why I have decided to ‘open source’ a lot of the information about it in my upcoming book.

Conclusion

Whatever differences there may be between the three frameworks, the one thing that they have in common is that they all emphasise the crucial need to focus training and development beyond legal knowledge and skills.

Having a framework and associated programs is important because it can convert an otherwise random grouping of theoretical courses on non-legal skills into something capable of being applied in various practical contexts more broadly and consistently. It also facilitates credentialing or certification that will eventually help to validate qualifications in this previously opaque area of professional development.

Ultimately, it is not the name of the framework that matters but rather the extent to which the framework, and the detailed programs and modules, meet your objectives, whether that is to just learn a few more skills to be better at what you do today or to truly facilitate human transformation to complement any digital transformation programs. The other critical factor is the qualifications and experience of the person delivering the program and how well they understand and can explain the application of the theory, to your unique work situation.

In a way, it is a bit like when you look in the mirror and ask yourself are you in the best physical shape for whatever it is you want to do. Once you’ve decided on your objectives, you then have a choice. You can pick a few exercises that you think are going to achieve your goals and do these on your own. Alternatively, you can sign up to a program designed by a health and fitness professional. You can then do the program on your own or with the help of a personal trainer to make sure that you are doing the exercises properly and keep you focused over the long term.

For something as important as your health or career, it is crucial to be clear about your objectives and take the time to become better informed about the different options to help you achieve your objectives. This article is intended to raise your awareness of the three primary options so that you can find out more about each one and make an informed choice about what shape you’d like to become.

[i] See, for example, The World Economic Forum 2018 Future of Jobs Report

[ii] https://www.weforum.org/press/2020/01/the-reskilling-revolution-better-skills-better-jobs-better-education-for-a-billion-people-by-2030/

[iii] The Future of the Professions: Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind, OUP Oxford 2015

[iv] Foundations of Practice: The Whole Lawyer study of over 24,000 lawyers in the US .https://iaals.du.edu/publications/foundations-practice-whole-lawyer-and-character-quotient#tab=what-makes-a-good-lawyer

[v] See for example Suffolk University’s Legal Innovation and Technology Certificate, University of Calgary’s Legal Practice: Innovation course, https://www.artificiallawyer.com/legal-tech-courses/ and the report compiled by Andrea Perry-Petersen on Innovation courses in Australian Universities – http://www.andreaperrypetersen.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Legal-Innovation-Education-Sep-2018.pdf

[vi] ‘Succeeding through Service Innovation’ – http://www.ceri.msu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Cambridge_T-Shaped.pdf

[vii] See David Guest, “The hunt is on for the Renaissance Man of computing,” The Independent, September 17, 1991. The concept was popularised by Tim Brown, CEO of Ideo, when referring to the type of person his famous design studio seeks to recruit.

[viii] See for example T-shaped graduates such as https://www.uow.edu.au/about/learning-teaching/academic-portfolio-update/april-2019-issue/what-will-a-uow-graduate-look-like-in-a-world-beyond-2030/ and https://www.studyinternational.com/news/leading-law-schools-that-produce-t-shaped-graduates-with-global-talent/

[ix] Peter Connor, “The T-shaped Lawyer’. ACC Docket July Edition 2017. https://www.legalbusinessworld.com/single-post/2017/12/22/The-T-Shaped-Lawyer

[x] https://www.oshapedlawyer.com/

[xi] Natalie Runyon, Shellie Reid, Cat Moon, Alyson Carrel and Gabe Teninbaum

Peter Connor

Peter Connor is the Founder & CEO of AlternativelyLegal. Using his 25+ years of global in-house experience, he has developed the unique T-shaped In-House Lawyer Framework™ and T-shaped Legal Team Framework™ In the last 5 years, he has used these Frameworks in his training and consulting work all over the world with more than 1000 in-house lawyers at brand name companies and government organisations to help them to reinvent themselves and to reimagine their way of working. Peter can be contacted at peter.connor@alternativelylegal.com