The rise of open innovation and open source software has caused some organizations to rethink long-established practices, including their attitude towards intellectual property (IP) and IP Rights (IPRs). Add to this the growing presence of insurance firms, lenders and venture capitalists willing to use IPRs as collateral for financing, and a definitive shift in mindset can be seen taking place.

To further fuel the trend, in late 2021, China announced amendments to its procedures to register patent pledges after the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) proposed a few amendments in its Proposal on Revision of the Patent Pledge Registration Method (Draft for Soliciting Comments), consultation period which closed on 10 August 2021.

The updated measures, announced in November 2021 (http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-11/17/content_5651398.htm), include provisions outlining what is needed to register a patent pledge, such as a contract (Art. 3), consent of all co-owners (Art. 4), and application requirements (Arts. 7-9), as well as provisions dealing with amendment (Art. 13) and cancellation (Art. 14).

Two Words, Two Meanings

It is important to note here that the term ‘patent pledges’ lacks a clear definition in general. Some may think of patent pledges as vehicles to be used by organizations to promote certain technologies, such as:

- IBM’s promise not to assert 500 of its patents against the development, distribution and use of open-source software

- Denso Wave Incorporated, which holds a number of patents on QR Code, allowing free use of the QR Code as long as the standards for QR Codes in JIS or ISO are followed

- Tesla CEO, Elon Musk, announcing, in 2014, that Tesla would not “initiate patent lawsuits against anyone” who uses their technology in good faith

However, patent pledges can also be viewed in terms of collateral for IP financing, and it is this latter definition that China’s legal drafters had in mind.

China’s introduction of these patent pledgerelated measures is not surprising as they help with the dissemination and development of new technology, outlined in China’s latest five-year plan which emphasizes technological independence and leadership in key technologies, such as AI, the Internet of Things, biotech, integrated circuits, and 5G and blockchain, along with lowering barriers to access technologies and financing for small firms and start-ups.

It is important to note here that the term ‘patent pledges’ lacks a clear definition in general.

Overall, China has increased lending support for the private sector, with new loans to private enterprises in the first ten months of 2021 reaching five trillion yuan (US$782 billion), according to a Xinhua report citing the nation’s top banking and insurance regulator. Furthermore, IP financing has been growing rapidly in China. In 2020, the total confirmed amount of patent and trademark pledge financing in China reached 218 billion yuan – a year-over-year growth of 43.9%, while the number of pledged projects grew 43,8%, to 12,093. COVID 19 accelerated this trend when CNIPA and intellectual property bureaus at all levels carried out a series of measures to promote IP financing.

The changes also dovetail well with the open licensing provisions of China’s updated patent law, whereby patent holders may grant non exclusive (but not sole or exclusive) licenses, while annual patent fees paid by patentees will be reduced or exempted.

This combination of changes will further help companies and individuals seeking financing using their IPRs. To avoid confusion, companies seeking to promote their technologies using promises not to sue may want to reconsider their nomenclature.

There is yet another potential benefit for the new registration system – it provides a backhanded way for inventors and companies to find out who has been providing financing for IP.

But this is only half of the matter. Lenders will need to do their due diligence before signing off on, for example, a loan backed by patents as collateral.

The Us And Other Counterparts

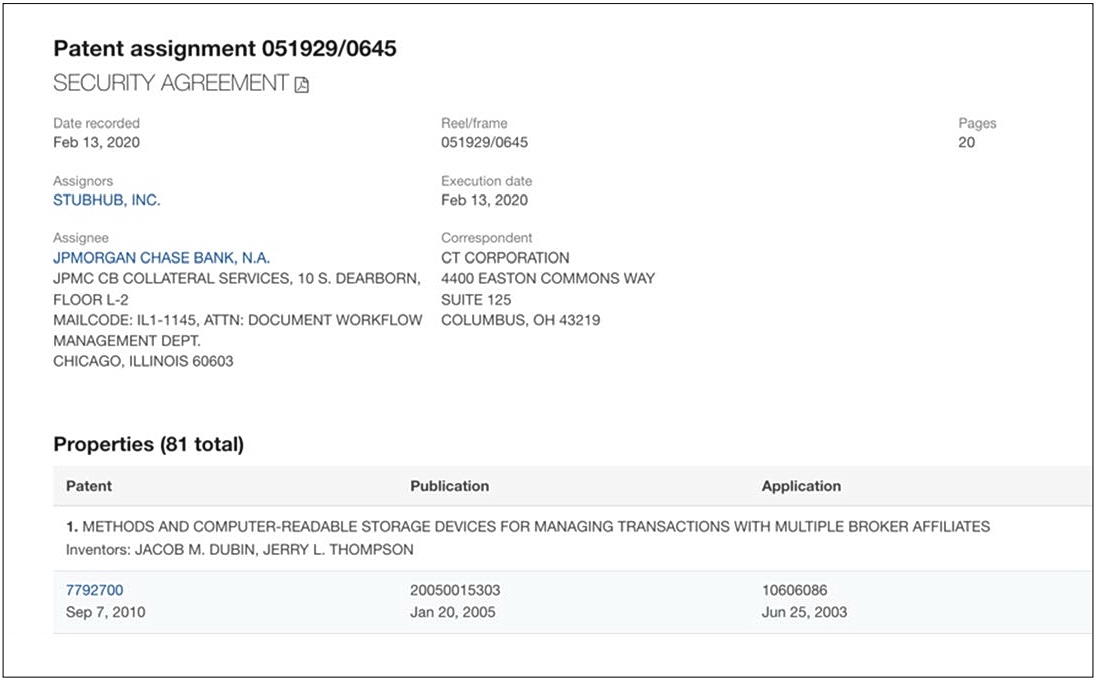

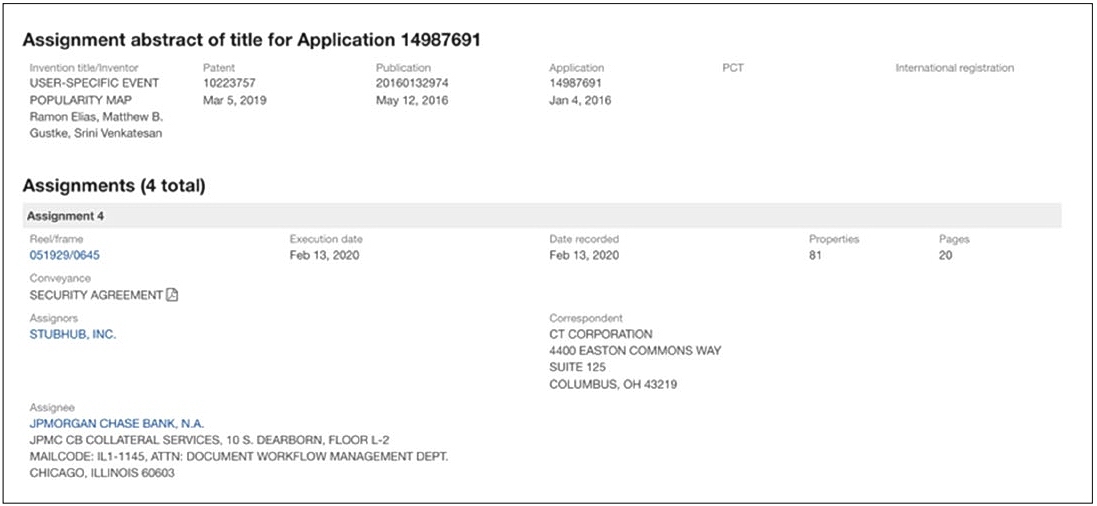

China’s patent pledge measures are actually nothing new. Other patent jurisdictions also track IP securitization. The US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), for example, tracks patents (or applications) pledged as part of a security agreement on its public database, but as ‘assignments’ rather than ‘patent pledges’. The sample illustrated here shows patents assigned to a bank – JPMorgan Chase – and a list of assignments pledged as part of a security agreement.

Having an up-to-date and easy to search, publicly accessible list of patents pledged as financial collateral (e.g. for a loan or venture financing), allows lenders to ensure that the same patent has not been pledged multiple times concurrently by bad-faith patent owners.

IP Valuation

The above complements the process of IP valuation as a pledge/assignment would add an additional wrinkle to an IP asset and thus potentially affect its value and, of course, some form of IP valuation would be needed as part of any IP financing exercise. IP valuation itself is a complex topic well beyond the scope of this article, but, suffice to say, valuing IP is not the same as valuing other assets, such as real estate, because of the business, technological-related (typically with patents but increasingly with some copyright protected content), and legal variables, including IP assignment or pledging risks.

Lenders – including not just banks, but also organizations providing IP-backed business funding (e.g. venture capital) – should ensure their loan evaluators understand the nature of IP value and that their due diligence procedures account for IP-related risks in addition to excessively pledged/assigned IP or events that impact the value of pledged IP.

New Caveats For Lenders

A patent pledged as loan collateral can be invalidated or openly infringed with devastating effects on its value, and the risks are not exclusive to patents. There are a multitude of potential risks for copyrighted works, including infringement (both primary and secondary) or disputes among joint authors or owners (something we see, for example, in the NFT space where sales of NFTs were halted due to disputes among joint authors of a work). Finally, if an IP owner cannot enforce its IPRs, the value of the IP may be eroded.

A patent pledged as loan collateral can be invalidated or openly infringed with devastating effects on its value, and the risks are not exclusive to patents.

There is a common joke among legal professionals that lawyers often like to start an answer with the words ‘it depends’ but, in the case of IP valuation, with the confluence of business, technological and legal considerations, the value of any IP really does depend on many things and, as noted above, can quickly change dramatically.

As more companies seek to offer their IP as collateral, lenders and counsel will need to start learning more about IPRs, particularly the related risks, and get comfortable with the inherent uncertainties involved.

Disclaimer: All views are personal and do not reflect that of the organization. The views shared are not intended for any legal advice and are for general information and education purposes only.

Ron Yu Ron Yu teaches intellectual property law and Fintech at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (where he also does research), the University of Hong Kong, and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology |

* This article was first published in the Feb 2022 issue of the IHC Magazine. You can read/download the magazine here.