INTRODUCTION

2023 will be a year of substantive climate change action as all EU market participants (EMPs) and China market participants (CMPs or together Financial MPs) will be accountable to comply1 with a plethora of rigorous and exacting disclosure requirements on how they are managing emissions.

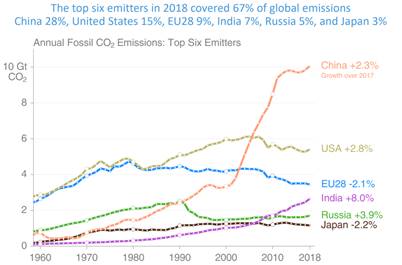

Given that China has been the largest CO2 contributor for the last decade2 and consistently responsible for nearly a third of the world’s emissions3 since 2018, it is in the best position to improve the global trajectory. The table below shows the top carbon emitters by jurisdiction.

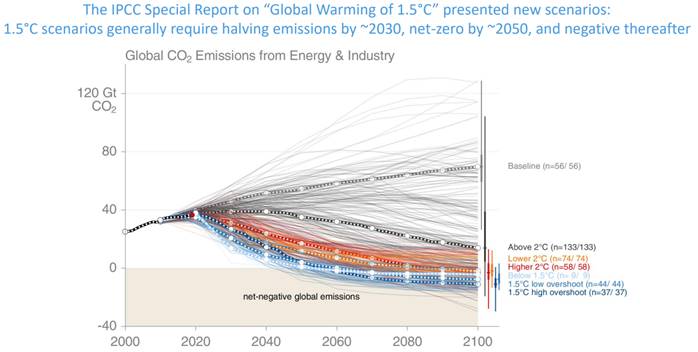

Accurate emissions measurement matters, given that significant change is required to adjust the current direction (shown below) and avoid impending issues caused by global temperature rise.

This article describes the complexity of emissions measurement among multinational corporates in China and their related investment community, given the dynamic multi-jurisdictional regulatory landscape. It then demonstrates the current issues and concludes with a practical means to navigate them.

GLOBAL REGULATORY MOVEMENT

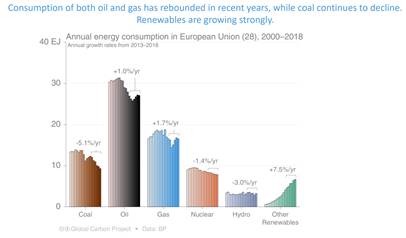

As mentioned, China and the EU have established significant systems (i.e., regulations and carbon measurement via their Emission Trading Systems (ETS)) that require immediate action from FMPs to meet 2023 mandatory reporting requirements.

2023 compliance deadlines should be feasible, given the impetus began in 2015 via COP214, where leaders5 pledged to have strategies implemented within five years. However, most regulatory announcements occurred around the five-year mark (2020) and have accelerated since. Most critical are the major emitters.6 Among them, the EU and China7 have made the greatest regulatory strides. Accordingly, FMPs in these markets are facing an imminent and arduous compliance feat.

For example, in March 2020, the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) standardised global climate change compliance by publishing the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR).8 The detailed requirements within include clear-cut quantification, timelines, and guidelines in alignment with the EU Taxonomy9 Regulation.10

In February 2021, these standards were further solidified as the ESAs11 published the Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS), including a reporting template to illustrate Principal Adverse Impacts (PAI) of investment decisions on sustainability factors.12 These disclosures focus on a set of 18 mandatory and 46 voluntary indicators applicable to corporates and investors.13

Finally, on 31 March 2022, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation, released its first climate-related disclosure requirements, providing a globally recognised accounting regime for consistent reporting.14

RECENT CHINA AND HK REGULATORY MOVEMENT

The combination of the above technical and financial disclosure standards provides an even global arena for measuring and reporting. This is particularly important so that regulators in all jurisdictions can speak the same language when reporting their progress on this global endeavour.

Given that China has the loftiest emissions challenges, such global standardisation is vital to efficient and effective regulatory benchmarking.

Accordingly, climate change disclosure pressures on CMPs have been mounting, with regulatory requirements escalating exponentially, especially following the 26th UN Climate Change Conference in November 2021 (COP26).15

Further, the fact that many corporates in China are listed in Hong Kong (HK), where local authorities have been assertively requiring climate change disclosure, makes for a particularly dynamic and challenging regulatory landscape to navigate,16 especially if entities are considered both EMPs and CMPs.

Below is a subset of 5 of the most relevant, recent and critical announcements in China since COP26, derived from financial and other relevant bodies:

1. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment’s (MEE) release on 8 February 2022, entitled “Measures for the Administration of Legal Disclosure of Enterprise Environmental Information”.17

These involve companies that produce a “high environmental impact” as well as those financing such projects. Obligatory disclosure is specified for high-emitting industries, such as thermal power generation, non-ferrous metallurgy, and other heavy industry. The list also includes companies with emissions that have surpassed the national caps or where environmental breaches have occurred. This performance is expected to be comingled with each company’s credit record rating as well.

2. The National Development and Reform Commission’s (NDRC) and National Energy Administration’s (NEA) 30 January 2022 release of opinions on “Improving the Institutional Mechanism and Policy Measures for Energy Green and Low-Carbon Transformation”.

These specify systems and policies needed for non-fossil fuel sources to meet future energy demands while replacing existing fossil fuels. This announcement follows a similar one from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology specifying how heavy industry sectors will achieve peak carbon emission before 2030 as well as the strict banning of hydrofluorocarbon projects.18

3. China Securities Regulatory Commission’s release on 12 April 2022, prescribing the implementation processes for carbon finance products.19

This lays the foundation for the China Certified Emission Reductions (CCER) scheme, projected to re-launch within 2022. It is expected to provide viable incentives within China’s ETS20, launched in July of 2021,21 to entice a wide array of FMPs to help reduce emissions and make a profit while doing so.

China’s disclosure situation is complex as many companies are HK Exchange issuers. This means these companies are subject to some of the most rigorous disclosure requirements globally

But China’s disclosure situation is complex as many companies are HK Exchange issuers. This means these companies are subject to some of the most rigorous disclosure requirements globally.

For example, the HK Exchange recently published:

4. “Guidance on Climate Disclosure” on 5 November 2021.22

This was published as there was a clear need to assist CMPs in assessing and reporting on their risks, given a lack of HK regulatory experience. Immediately after the above, a more stringent requirement was co-published by the HK Monetary Authority and Securities and Futures Commission, as follows.

5. “Financial impact of climate change on businesses” on 30 December 2021.23

This is expected to be complied with by 2023 and is aligned with the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), while corresponding with other Asia regulators.24

ISSUES AND ANALYSIS Given the above more stringent and technical climate change disclosure requirements of SFDR and the RTS along with the China regulations mentioned above, FMPs need accurate data to make disclosures on all the mandatory and voluntary indicators related to both environmental and social adverse impacts across asset classes.25

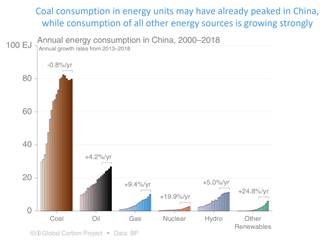

However, it is a complicated landscape and China’s climate change challenge is unique, given its carbon footprint is mainly from power generation and heavy industry (80%), compared to Europe with 55% from the same sectors. Shown below, given China’s massive coal usage, a minor reduction should have a major global impact.

Accordingly, there is a critical role for China’s top industrial emitters which are expected to mainly rely on renewable power, clean hydrogen, and carbon capture to manage emissions.26

In addition, the corporations and investors in these high-emission sectors are playing in a particularly complex regulatory ecosystem with intense pressures to measure, calculate, validate, and trade on their carbon footprint.27

As mentioned above, key to the sustainable success of China’s ETS is the CCER. Normally such would consist of carbon allowances and carbon credits. Allowances limit the emissions a company can make, and when a company does not make use of these allowances, it can sell them. In the interim, credits can be earned by a broader range of FMPs for reducing emissions. Endeavours to reduce emissions could be lucrative, as credits can be sold on the carbon market.28

The re-launched scheme is anticipated within 2022. The initial CCER scheme was terminated in 2017 due to a lack of “trading volume and standardisation in carbon audits”29. Said another way, the previous CCER was not profitable and not reliable as falsified emission data was widely discovered.

The CCER “reboot” is expected to establish improved incentives and controls, creating a vibrant and trusted carbon trading marketplace for all relevant industries. But concerns persist that the carbon price30 and penalties31 will remain too minor to attract involvement and prevent breaches. Further, emission allowances are said to be too high for China to meet emission targets.32 That said, the ETS (only including power generation) has already achieved a 99.5% compliance rate within 2021.33

The CCER “reboot” is expected to establish improved incentives and controls, creating a vibrant and trusted carbon trading marketplace for all relevant industries.

Emission data, as mentioned, is the most significant issue as the data provided has historically been published directly by the emitting companies,34 thus it can easily be falsified. Indeed, this is what has occurred.35 In fact, this is the main reason other high emitting sectors beyond energy production have been delayed for ETS inclusion, perhaps until 2023.36

That said, in June of 2022, Li Gao, head of MEE committed to “ensure quality before relaunching”.37 In further support of this, referring specifically to the CCER trading mechanism,38 Liu Hong Ming, senior manager of global climate change at EDF China, stated that China must have “legal systems and supporting institutions for the rebooted CCER, as it strives to secure the integrity of the credits”.39 However, an official from the China Quality Certification Centre, Yu Jie, asserted that standards and methodologies are not enough. She stressed that only with enough competent professionals “having the necessary expertise and capabilities and a sound management mechanism”40 can integrity be assured.

Many have cited that data and the collection, analysis, calculation, and verification of such are a major challenge in China. Consequently, there has been much development in this area from government agencies such as those listed above (i.e., MEE, NDRC and NEA).

Many have cited that data and the collection, analysis, calculation, and verification of such are a major challenge in China.41 Consequently, there has been much development in this area from government agencies such as those listed above (i.e., MEE, NDRC and NEA). And, given the widely discovered issues, the MEE has cited a need for the use of third-party service providers (i.e., independent China-based ESG and climate change consultancies) who will likely require certification to help ensure quality and integrity.42

The service providers may range from verifiers and auditors to legal and advisory professionals, as well as tech experts which also help facilitate trades. The Big 4 consultancies are all in, as well as specialised consultancies such as China-based CECEP.43 However, there are two relevant and notable independent climate change advisors that stand out, with having both “on the ground” capacity and international exposure. These are GSG (Governance Solutions Group)44 and Deloitte China Risk Advisory (who recently acquired Carbon Care Asia45).46

These advisories both have dedicated teams in China, focused on dissecting detailed requirements and global standards such as the SFDR and RTS. They also provide stakeholders with flexible and comprehensive carbon accounting software and methods to collect data to confidently report on the organisation’s full emissions picture across Scope 1-2-3. With Chinese local as well as global multidisciplinary talent from legal, finance, accounting, and environmental technical specialists, they are abreast of the dynamic regulatory landscape in China and can also facilitate data collection efforts by EMPs concerning their China assets.

GSG also has a substantive database of Chinaspecific market and economic data, providing Chinese issuers and investors the ability to quantify their (or their portfolio’s) carbon footprint and proactively improve climate risk management ahead of a regulatory inquiry. What makes this database and calculator significant is that it is aligned with global methodologies such as Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials47 and Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures48 as well as China’s National Centre for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation.49 Given the influx regulatory complexity mentioned above, such multifaced alignment is key to ensuring that the measurements are consistent and aligned across a multitude of measurement schemes.

CONCLUSION

Given the dizzying pace of climate change regulation since the November 2021 COP26 summit, staying current, let alone competently navigating the multifaceted regulatory compliance landscape, has become daunting.

From the EU Taxonomy and SFDR/RTS requirements to the collection and calculation of carbon impact, the technical expertise on both a global and local level is paramount. Such complexity, if not properly managed and verified, can lead to falsified data, as we have already witnessed in China. However, given the amount of data and requirements from numerous regulators, it may be challenging for any given FMP to accurately represent their China and/or EU carbon footprint without the use of advanced data analytics along with verification from independent, external assistance.

Looking forward, the use of AI and blockchain enabled technology will help efficiently and effectively measure carbon impact. Climate Change accounting infrastructure is in the nascent stages but developing quickly with financial institutions providing trading platforms and financing for projects that generate carbon credits. HK, for example, given its fintech hub status, may be an early developer of blockchain to “digitalise the full carbon credit lifecycle to optimise operational efficiency, as well as to maintain the registry to enhance transparency and traceability.”50

The above, along with licenced external professional advisory, may become a more practical method for companies and the investment community to steer clear of disclosure liability as well as maximise carbon credit returns.

As mentioned, 2023 is when the much-anticipated compliance requirements become mandatory. While there has been a reasonable ramp up period, it seems many organisations, investors and advisors will still struggle to meet the ever-increasing compliance demands.

Mark D. Schroeder

Mark has been providing legal and regulatory advisory in China and Asia for more than 20 years. His practice includes corporate governance, with a focus on ESG integration and compliance consulting often involving data issues, including data privacy, data protection, cyber security, and disclosure mechanisms. Based in Hong Kong, he is a strategic advisor to GSG (Governance Solutions Group) on data related ESG complexity.

- https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/ sustainability-related-disclosure-financial-services-sector_en

- CDIC: Peters et al 2019; Fredlingstein et al 2019; Global Carbon Budget 2019 – All attached charts are from the same source. See also: https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/carbonbudget/archive/2019/GCP_CarbonBudget_2019.pdf

- 30% in 2020 and 27% in 2020, as reported by Rhodium Group https://rhg.com/research/ preliminary-2020-global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-estimates

- Pan, J. (2022). Post-Paris Process: A Transformational Breakthrough Is Still Needed. In: Political Economy of China’s Climate Policy. Research Series on the Chinese Dream and China’s Development Path

- 193, meaning 192 countries + the European Commission

- China, US, EU-27, India, and Russia (five largest emitters). See also: Beusch, L., Nauels, A., Gudmundsson, L. et al. Responsibility of Major Emitters for Country-Level Warming and Extreme Hot Years. Commun Earth Environ 3, 7 (2022)

- China is the largest emitter by a significant margin. Its pledge for net zero by 2060 accounts for more than 60% of the emissions among countries that have pledged. China’s overall share of global emissions was 30% as of 2019. See also: www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/gs-research/carbonomics-china-netzero/report.pdf

- Updated further in March 2022 to provide even more detail and interim requirements to help market participants become compliant by the January 2023 deadline. See also: https://www.eba.europa.eu/ esas-issue-updated-supervisory-statement-application-sustainable-finance-disclosure-regulation

- The EU Taxonomy is a 550-page classification system for economic activities that are environmentally sustainable. The purpose is to help EMPs prevent green washing with its detailed categories and to help them identify and invest in sustainable assets with more confidence. See also: https://www.spglobal.com/esg/insights/a-short-guide-to-the-eu-s-taxonomy-regulation

- Specifically, Article 5 and 6, covering how and to what level investments underlying their financial products are in economic activities qualified as environmentally sustainable.

- The three relevant ESAs are the European Banking Authority, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority and the European Securities and Markets Authority.

- Sara Sundqvist, “EU Taxonomy and Sustainable Finance: Key Levers for Climate Change Mitigation”, University of Turku, School of Economics, 15 February 2022, at page 52 para 1 and 2. See also: European Commission, Sustainability-related disclosure in the financial services sector; European Commission, Strategy for financing the transition to a sustainable economy.

- Rocio Redondo Alamillos and Frederic de Mariz, “How Can European Regulation on ESG Impact Business Globally?”, Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 30 June 2022, at pages 10 and 11.

- The IFRS founded the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) to focus on climate change in November of 2021.

- The 2021 UN Climate Change Conference, referred to as COP26, was the 26th such conference, this time held in Glasgow (31 October to 13 November 2021) and led by UK minister Alok Sharma https://ukcop26.org

- Referring to numerous announcements from HKMA, SFC and HKEx. The latest one is from June 21st, where they announced that they are in the process of implementing ISSB standards for HK listed companies. See also: https://www.hkma.gov.hk/eng/ news-and-media/press-releases/2022/06/20220621-5

- https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk02/202112/t20211221_964837.html

- https://www.ciftis.org/article/11468649790566400.html

- www.csrc.gov.cn/csrc/c106311/c1955407/content.shtml

- A trade on the platform run by the Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange.

- The first round of the scheme included 2,225 entities in the power generation sector and is intended to extend to aviation, metals, steel and other construction materials, as well as chemicals, petroleum and paper. Timeline is not confirmed.

- 2 November of 2021 – https://www.hkex.com.hk/-/media/HKEX-Market/Listing/Rules-and-Guidance/Environmental-Social-andGovernance/Exchanges-guidance-materials-on-ESG/guidance_climate_disclosures.pdf

- December 30 of 2021 – https://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/doc/key-information/guidelines-and-circular/2021/20211230e2a1.pdf

- Lim, Ernest and Varottil, Umakanth, “Climate Risk: Enforcement of Corporate and Securities Law in Common Law Asia”, 27 May 2022, NUS Law Working Paper No. 2022/006 at page 7.

- “Clarifications on the ESAs’ draft RTS under SFDR”, Joint Committee of the European Supervisory Authorities, 2 June 2022. See also: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/jc_2022_23_-_clarifications_on_the_esas_draft_rts_ under_sfdr.pdf

- Michele Della Vigna et al, “Carbonomics, China Net Zero: The clean tech revolution”, January 2021 at page 8

- Main industries are stated as: coal, electricity, iron & steel, nonferrous metals, petrochemicals, chemicals, and building materials. In “Responding to Climate Change: China’s Policies and Actions”, The State Council Information Office of the PRC, 27 October 2021. See also: http://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/32832/Document/1715506/1715506.htm#:~:text=China%20 has%3A&text=strengthened%20the%20management%20of%20targets,and%20non%2Dferrous%20metal%20sectors.

- Xu Nan, “Rebooting China’s Carbon Credits: What will 2022 bring?”, 9 June 2022, China Dialogue. See: https://chinadialogue.net/ en/climate/rebooting-chinas-carbon-credits-what-will-2022-bring

- In March 2017, the NDRC issued a notice. See also: Xue Yujie, “What is the China Certified Emission Reduction Scheme and Why is it Important for Beijing’s Carbon Neutral Goal?”, South China Morning Post, 31 January 2022.

- 2021 price per ton was 50 yuan at launch, 54.22 in December and is expected to rise to 65 in 2022 (Refinitive 2021). The price should reach 156 RMB ($24 USD) by 2030. See: Barrett, Eamon (2021-07-16), “China’s New Carbon Emissions Trading Market Already Needs Reforming”, Fortune.

- If an entity fails to report data (or falsifies data), they will be subject to a fine of 10,000-30,000 RMB ($1,449-$4,347 USD); if they fail to keep their emissions below their allowances, they will be subject to a fine of 20,000-30,000 RMB ($2,898- $4,347 USD). All emissions that are over the entity’s allowances/compliance obligations will be deducted from the next year’s allowances. See: International Carbon Action Partnership (18 May 2021). “China National ETS”, International Carbon Action Partnership.

- Gray, Matthew, “Turning the Supertanker”, 15 April 2021, TransitionZero.

- Reportedly 2,162 complied to achieve the 99.5%; some of the initial 2,225 must have been closed. See: XUE, Yujie, “China’s Carbon Neutral Goals: Turnover Under Emissions Trading Scheme Expected To Reach US$15 Billion In 2030”, 2 February 2022, South China Morning Post.

- Ibid from Gray, Mathew, 15 April 2021.

- MEE reported 4 cases beyond the initial one discovered. See: www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/ydqhbh/wsqtkz/202203/ t20220314_971398.shtml

- Li, P., Zhang, H., Yang, C. and Zhang, J., “Carbon Emission Trading Scheme Pilot Program and the Degree of Corporate Environmental Information Disclosure: Evidence from China”, 2022, at Page 47.

- “National Carbon Market Expansion May Be Delayed To 2023”, China Dialogue, 19 May 2022. See: https://chinadialogue.net/en/ digest/national-carbon-market-expansion-may-be-delayed-to-2023

- Hou Liqiang, “China Set To Relaunch Carbon Cut Program”, China Daily, Hong Kong Edition, 14 June 2022

- Ibid

- Ibid

- John Johnson, “China’s New ETS A ‘Sleeping Giant’”, September 2021, CRU. See: https://sustainability.crugroup.com/article/ chinas-new-ets-a-sleeping-giant

- Ibid from footnote 28, Xu Nan

- www.cecepec.com/En/

- http://governance-solutions.com/

- https://environment-analyst.com/global/107808/deloitte-acquires-hong-kong-based-carbon-consultancy

- For full discloser, I have previously worked at both Deloitte China and Governance Solutions Group so I understand these two China based advisories better than others.

- https://carbonaccountingfinancials.com/testimonials

- www.fsb-tcfd.org

- www.ctc-n.org/about-ctcn/national-designated-entities/national-center-climate-change-strategy-and-international

- “Carbon Market Opportunities for Hong Kong Preliminary Feasibility Assessment”, Green and Sustainable Finance CrossAgency Steering Group Carbon Market Workstream, HKMA, HKEX, HK SFC, Environmental Bureau, Financial Services and Treasury Bureau, March 2022 at paragraph 29 and 30. See: www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/doc/key-information/pressrelease/2022/20220330e3a1.pdf

This article was published in the September, 22 issue of the IHC Magazine. To read the fill magazine, please click here